A Geometric Theory of Coding with Vibes [part 2]

In which we continue down the path of trying to figure out, from first principles, what is really going on when we pair program with machines.

In part 1, I made the case that the important value of an LLM might not really be “intelligence” but the ability to “stick to the task” (aka instruction coherence) as more data is added to the context (either by us interacting directly with the agent, or by tools the agent invokes).

Before we try to peer into what might be going on in these models when they’re coding with us, I want to turn it around and look at it from the other direction: what would it take to build a “pair programming machine” from first principles?

Such a machine, in theory, needs only three high level components:

a way to for us describe requirements

a way to for it to generate new programs

a way to evaluate fitness of the program to the requirements

We could potentially write all software with this machine but there are many problems with it:

describing requirements and evaluating fitness often means writing another program… and if we wanted a machine to write that, we are now stuck in a recursive chicken/egg loop.

there is no feedback loop… the machine would spit out new programs and they would either pass the fitness test or they wouldn’t. But when they don’t, there is nothing the machine is obtaining from this run except that this particular “specimen” didn’t work.

The result is that such a machine would be stupendously impractical because of the sheer number of “monkey typing” attempts that it would need to try. Sure, given enough monkeys and typewriters, we would get Shakespeare but not within a useful amount of time and energy.

The monkey typing programming machine won’t work, but let’s ask ourselves: what can we do to make it better?

Warmer

An crucial inefficiency of the monkey typing programming machine is that failure does not influence the next attempt. Each attempt is effectively uncorrelated which means that the only practical strategy is to try every possible thing.

A fun game to play with little children is to hide something in the house and ask them to find it. All parents know that they grow tired of it if they don’t find quickly what they’re looking for. One universal way parents make this form of play more engaging is to use “warmer/colder” signals. Warmer when they’re getting closer, colder when they’re getting further away.

The moment we say “warmer”, we are offering a “gradient”, a localized partial information toward the goal. The game changed from “look in every single place in the house” (which they quickly realize would be tedious and boring) to “follow the gradient” (which kids find much more intriguing).

What would it mean to add a “gradient” to our coding machine? We need to add a fourth component:

a way to for us describe requirements

a way to for it to generate new programs

a way to evaluate fitness of the program to the requirements

a way to encode fitness failures as additional requirements

On the surface, this machine looks very similar to the previous one but the introduction of this last component changes its nature in transformative ways because program generation goes from being “random” to be “guided”, just like our child’s play went from being “search in every corner of the house” to “climb the gradient”.

Ok, cool, but how would we achieve this?

An important thing to realize is that human programmers effectively operate like this machine already. We obtain requirements, we write the program, we run the programs, we observe failures, we go modify the program… we rinse and repeat until fitness failures go to zero (or small enough to be tolerable).

Imagine a system in which our tests passed or failed but without any additional signal. No logs, no compiler or linter output, no type checking, nothing. Just “pass/fail”. Programmers know these are nightmare debugging scenarios as they are very hard to work with (precisely because they offer no success gradient).

We praise compilers that give us very good instructions on what’s wrong with our program (the rustc compiler, for example). So much in fact, that we find it infuriating that that a compiler tells us that a line is missing a semicolon. If you knew that, why don’t you just add it yourself and keep going?!

What we have been missing is a way to automatically bridge this part of decoding the fitness failure signals (compilers and linters output, tests results, crash reports, runtime logs, exception stacktraces, dashboards plots, alerts, etc) into something that can be used by a machine to tweak a program in the direction of the gradient obtained by the failure signals.

But what does it mean in practice to modify a program in a gradient direction?!

It’s one thing to be able to interpret “this line is missing a semicolon” and turn that into an action that adds the right character to that line but what if the test is failing 2 out of 100 times and now we know it’s flaky, we could glean that realization from the test output but then, what does it mean to modify a program along the “flaky” gradient?

Embeddings

This is where we need to talk about embeddings.

I won’t go into a deep mathematical treatment for this (you can find good ones everywhere on the internet, say here) but the very succinct TL;DR is this:

embeddings are a way to turn words into points in a space in a way that some of their semantic relationships end up encoded in the geometry of the space

Yeah, I know, you have no idea what that means or why that would be useful.

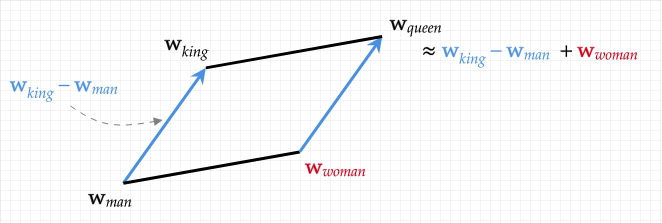

Let’s use an example to make it stickier: an embedding is a map between words and points into a geometric space. This map “embeds” words into this space. If we take the word “king” and we get its point and the word “men” and its point, the difference between these two points gives us a “direction” (from “men” to “king”). If we then take the point of “woman” and we move in this same direction we find the point for the word “queen”.

So, in practice, by subtracting “men” from “king”, we found the geometric direction of “royalness”… so that if we start from “women” and we move in that direction, we find the royal version of “woman” which is “queen”.

The original Word2Vec paper (from 2013) is spectacularly dry in its value and many missed its importance for years but effectively gave us a with a way to build these embeddings efficiently. This became the starting point of bridging the semantics of symbols (words and entities, which live in boolean and rules spaces) to a more “differential” place where we can operate in more geometric spaces with “gradients”, “directions” and “distances”.

With this conceptual bridge from sequences of words to geometric spaces, the idea of “moving a program in the direction of less flaky test” all of a sudden doesn’t seem so impractical.

Embedding Computers

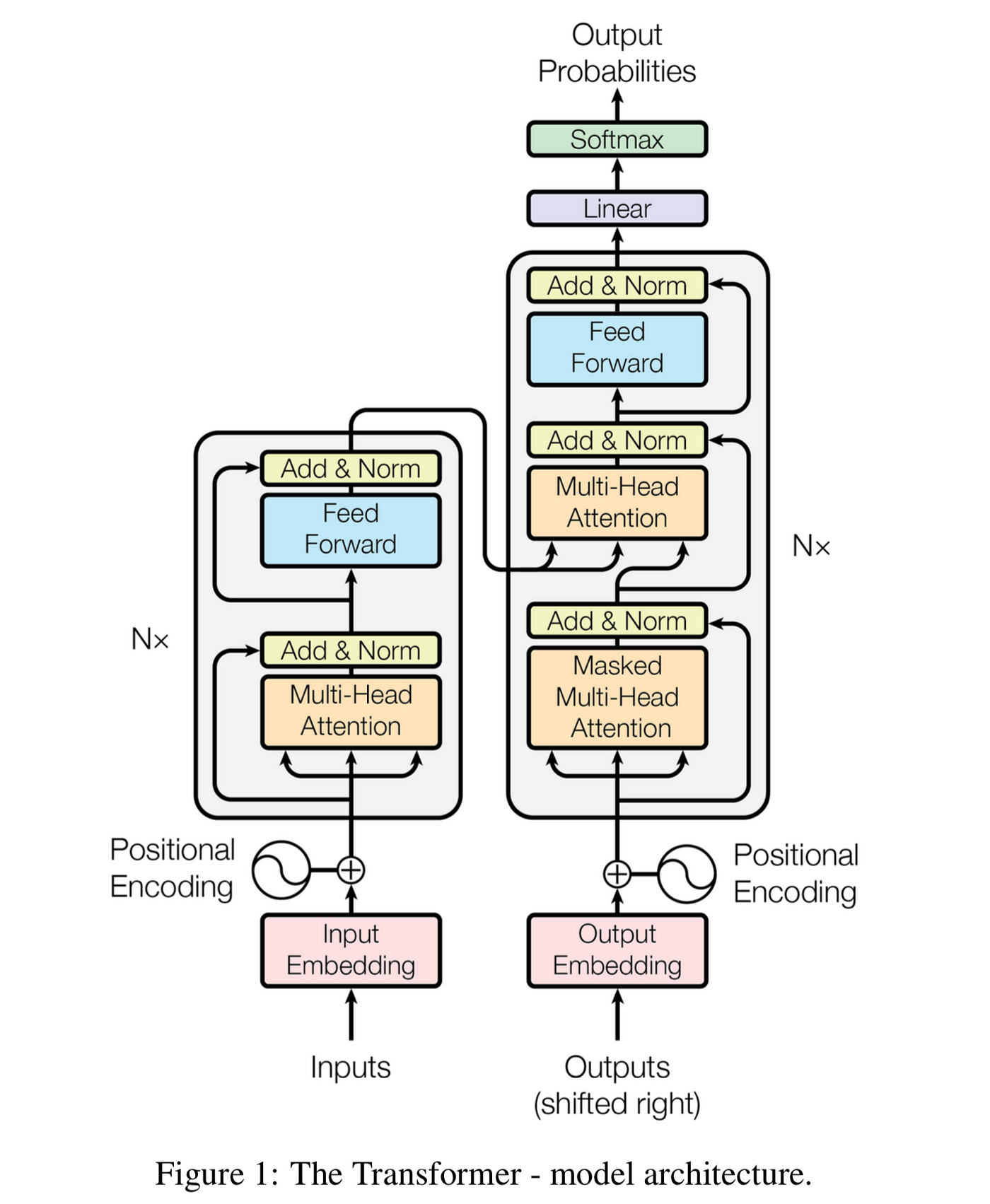

Transfomers are the foundation of every frontier LLM today and they are effectively “embedding computers”. They were designed specifically for natural language translation and they effectively were conceived to “transform” one natural language into another.

The basic idea was to build a computer that was able to operate on embeddings instead of operating on logic gates and then instead of programming it by hand, just feed it lots of data from one language to another and let it learn from the data the kind of embedding manipulation operations that were required to perform natural language translations.

We feed pairs of translated literature into this system and it learns a geometric “lingua franca” of “directions” to use to turn one sequence of words into another. So, not just “hello” into “ciao” but entire sentences in which the literal translation might actually be wrong.

For example, Italians say “fuoco” (fire) to kids instead of “warmer” and “acqua” (water) instead of colder. So a machine that translated “the parent said warmer to the kid” to the Italian “il genitore disse piu’ caldo al bambino” would be creating a misleading translation even if technically a dictionary would agree with each translated word pair. As human translators know very well, the context of where the word “warmer” was used matters as much as the word itself.

My sense is that the reason why transformers were so much better a natural language translation is that they were able to model deeper semantic meaning of words. Not just the words themselves, but their place in context (see also attention).

For decades, NLP system failed to have enough modeling capacity to parse things like “complex complex complex” (a somewhat artificial yet meaningful way to indicate the fear of complicated buildings). Transformers changed all that by avoiding operating in the space of words and instead operating in the space of the embeddings of those words. After there is enough “semantic depth capacity” to embed something like “complex complex complex”, natural language parsing became a solved problem.

I believe this is what is happening to coding agents.

These machines are not operating in the space of language symbols (characters) or programming symbols (variables, functions, classes) but they are operating in the space of the embeddings of the components that make up software programs as emerged from their training in trying to predict how to autocomplete code.

Syntactic vs. Symbolic vs. Semantic

The thing is: nobody really knows what’s going on in the brain of a human programmer and nobody really knows what’s going on in the frontier models when they spit out code. There is just too much going on if we focus on the single neuron or neural network parameter. But after spending tens of thousands of hours interacting with human programmers and hundreds of hours interacting with machine programmers, the model emerging in my head is one of machines that are not really “reasoning” in the program symbolic space (like humans try to do, slowly and expensively) but rather “moving embeddings along directions gleaned from instruction and context”.

Here is crisp example that happened to me just this past week that hints to that: the LLM wrote a fragment of code and a linter corrected it (added a “const” prefix to a C++ variable that was never changed in a block). I then told the LLM to re-read the code and move that logic somewhere else. The agent moved the fragment but the “const” added by the linter was gone (the linter had to add it again later).

What this suggests to me is that something like this is going on:

the agent read the code and “parsed it” into its internal representation

its internal representation didn’t have the “const” part

the agent understood my instructions and translated them into “movement” of these internal representations

the internal representation was “moved” as a result of my instructions

the “moved” representation was then decoded into code; movement in the semantic domain (internal representation) ended up also reflecting as movement in the syntactic space (chars moved from one place to another), but the “const” part was missing.

This is not an operation on the syntactic space (like, say, “copy/paste” would be) or an operation in symbolic space (like, say, an advanced IDE would perform the renaming of a variable thru out the codebase). This feels like a third thing entirely: a geometric operation in semantic space with encoder/decoders bridging it to/from the syntactic domain.

Automation vs. Augmentation

Let’s use this hypothesis now to see how it can help us with our first principles coding machine:

a way to for us describe requirements → this would be us describing them in natural language.

a way to for it to generate new programs → this would be the machine able to move to and from the syntactic space to the semantic space and perform movement in the semantic space based on our requirements and instructions in natural language.

a way to evaluate fitness of the program to the requirements → this is a way for the machine to construct tool commands, execute them and capture their output.

a way to encode fitness failures as additional requirements → this is a way to parse the output of fitness tools from syntactic space into semantic space and turn them into further instructions/requirements.

The difference between a “large language model” and a “coding agent” is the introduction of #3 which, before, was done by hand by humans. This apparently simple change allows the agent to perform the entire loop on its own… as long as it’s able to remain “coherent” with the original requirements as more and more data is added to the context. We call performing this loop “reasoning” even if we really don’t know how much reasoning is really going on (or how much it is required for the fitness loop to converge).

What’s interesting to realize here is that there a fork in the road that emerges:

on one hand, a machine that has such a rich, detailed and established internal semantic space that it aims at “one shot”-ing the production loop (spending a lot of effort in doing the right thing from the start)

on the other, a machine that has a very strong focus and instruction coherence and doesn’t care at getting right the first time but to converge as quickly as possible to desired outcome (spending a lot of effort in “staying on target” but not much on each attempt).

The S-curve Ceiling of Sample Inefficiency

Scaling laws whisper to us that as long as we have enough data to feed these models and enough compute and memory, we can just make bigger and bigger models that will learn more and more nuanced internal representations and make the machine better at “one shotting” the fitness loops. This is the holy grail of coding automation.

The problem with this idea is that these models are very sample inefficient during training: they need many examples (hundreds if not thousands) unseen syntactic representations before they are able to construct internal semantic representations for them. It doesn’t matter if the “scaling laws” hold true in abstract, but if we run out of data to train, there is nowhere to go.

Another entirely different direction would be to make model be just “good enough” with it internal semantic representations and focus entirely on making the machine perform the loop more quickly and more stably.

What would this look like? Effectively we would need:

a language model that is only good at parsing the language we use to communicate with other human programmers and the tools use to communicate with us. (For many even around the world, that would be English) and doesn’t use any internal representation to memorize facts or things that can be looked up with tool usage.

a language model that is trained to predict all “changes” for all projects for all languages (so not just learning to predict the structure of code but learning to predict “code motion” in the semantic space, which is what humans do when performing “code reviews” on PRs/CLs/diffs)

a language model that is fine-tuned for instructions following and tool invocation

a language model that is fine-tuned for internal consistency and task coherence over time

The frontier AI labs are all chasing AGI thinking that once a model is good enough at everything, it will be good enough at coding too… but there are strong indications that the scaling laws are hitting their s-curve ceilings (because of data or compute restrictions) and my sense is that is not going to age well without significant architectural innovation in the sample efficiency space (and once the datacenter “braggawatts” clash with the harsh reality of token profitability).

Personally, I would be investing into making smaller models that don’t consume internal modeling capacity memorizing facts or intricate internal representations of code but just operate well enough within their try/fail “follow the gradient toward fitness” loops.

At the very least, research in this direction would allow us to better understand how much “reasoning” in terms of “embeddings computation” is needed to perform well in these “follow the fitness gradient” scenarios.

My personal experience suggests that even minor improvements in “task coherence” had dramatic utility effects for these agents. Claude Sonnet v3.7 was an improvement over v3.5 in task coherence but it was Claude Sonnet v4.0 that really changed the game for me. The task eval numbers improved but not dramatically, it was a minor step change in terms of “model intelligence” overall but it felt transformative as a user of coding agents built on top of it and it mostly had to do with the ability to stay consistent for much longer during the try/fail gradient loop execution.

Ok, fine, but few of us are actually building these machines and they are available already so, can we learn anything from this to make us better users of these existing tools?

I will cover this in part 3.