A geometric theory of coding with vibes [Part 1]

In which I try to explain the model that is forming in my head about what it's going on when we pair program with machines.

In my previous post, I highlighted the difference between “vibe coding” and “coding with vibes” which I believe can be summarized in a nutshell like this:

vibe coding is about delegating all development to the machines, including all risk management.

coding with vibes is using the machines to help us write the software while remaining firmly in control of the downstream risks.

It would be difficult to recognize the difference by looking at a sped-up video of a screencast. On the surface, they would look the very same: english goes in, code comes out and stuff happens.

The difference, I believe, is the mental posture.

With vibe coding, we’re navigators: we care about the destination but not the path taken. When coding with vibes, we are orchestra directors: we care about both and we retain control and intention, but operate thru others.

If we believe these machines to be “intelligent”, remaining “in the loop” feels detrimental, a form of “micromanaging”. The classic failure of junior developers learning how to manage the risks associated with not being aware and in control of every aspect of the execution.

But if these machines’ intelligence is an illusion, a mirage of their natural language propriety, failing to remain in the loop can lead us to even worse outcomes: fragile prototypes which crumble under production pressure.

Language != Intelligence?

Humans are fascinated with things that feel obvious and are yet hard to pin down. Intelligence is one of those things. I’m a huge fan of the work of François Chollet in this vicinity (see his “on the measure of intelligence” paper, as well as the delightful ARC-AGI effort, which I covered in the past).

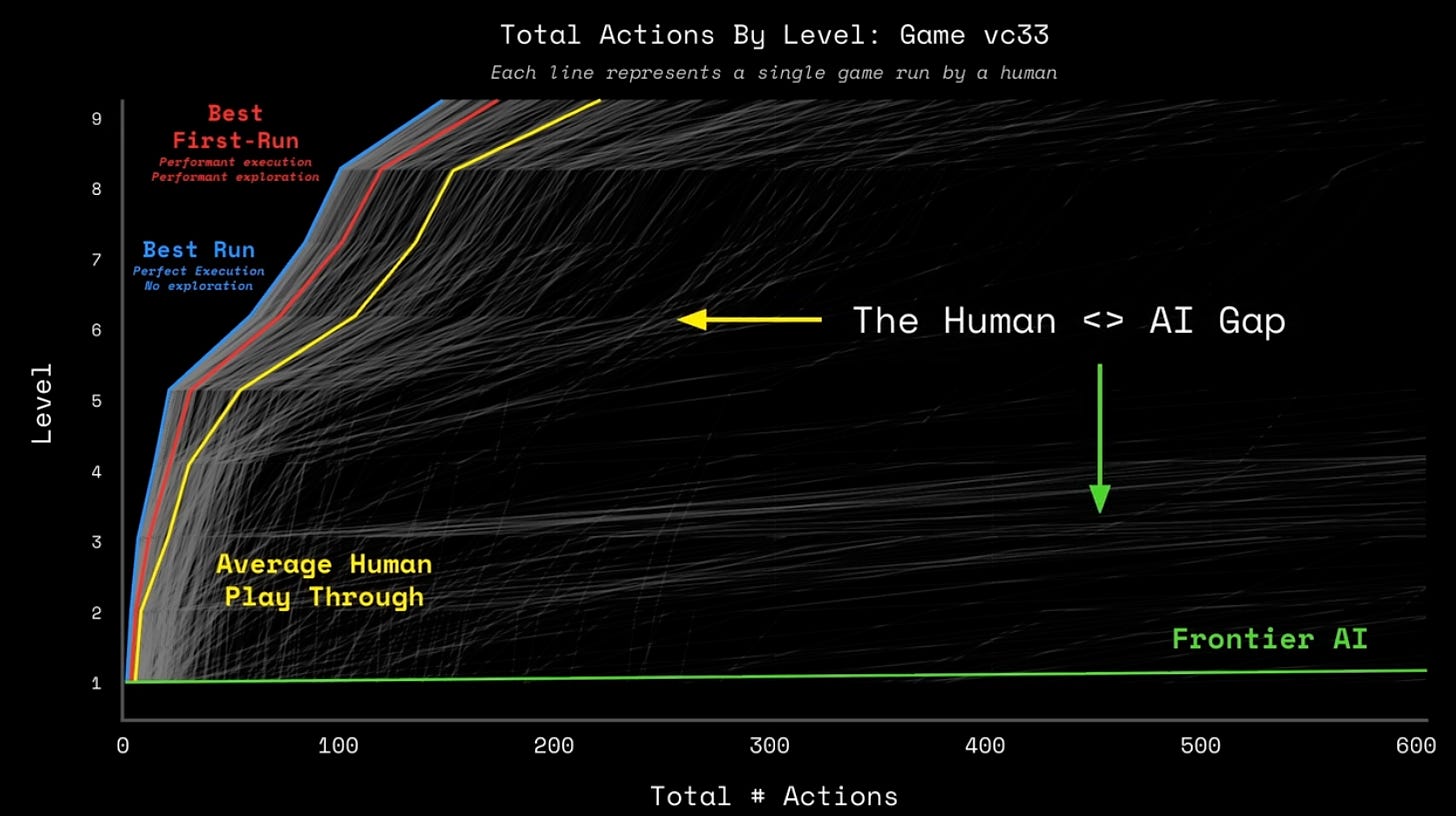

If there is one slide that describes this, I feel it’s this one from their recent talk about the upcoming ARC-AGI 3 benchmark:

This is a plot of all of the action trajectories of agents (both machines and humans) trying to solve an interactive puzzle (basically video games without any language hints). Yellow line is “average human”. Green line is “best in class language models”.

How do you feel about Claude Code managing your production risks after looking at that chart? Did your heart rate go up? Good, let’s dive deeper.

The principle of least surprise

I’m going to sidestep the entire philosophical tarpit around intelligence and instead operate uniquely on utility with these observations which I believe to be true based on my own empirical analysis:

these machines are able to understand natural language instructions enough to translate them consistently into action (both to generate new data and to operate tools to gather more context) in ways that generally don’t surprise me

these machines are able to read and digest large quantities of language, both natural and structured, and summarize it in ways that generally don’t surprise me

these machines are able to map concepts from one language to another (both natural and structured) in ways that generally don’t surprise me

these machines are inherently probabilistic, the same exact input will not generate the same exact output every time, but it will be different in ways that don’t surprise me (they feel “close together”)

I’m using “generally doesn’t surprise me” as my measuring stick and while it’s a blunt instrument, it’s enough to give us a foundation to work with. For example, Clippy, Eliza and Cyc would score poorly on every one of these dimensions so it enough resolution power to discriminate tools that “feel dumb” from those that don’t.

Constraint Satisfaction Problems

My working hypothesis is that programming digital computers is a mix of “literature” and Constraint Satisfaction Problems (CSPs) solving and that we are using LLMs for their “literature” abilities and ignoring the fact that they are terrible at solving CSPs (and they have no self-awareness of that!)

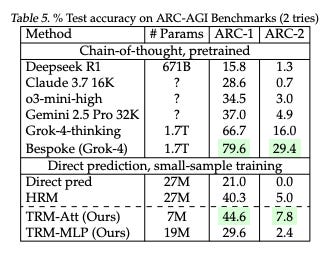

For example, look at this table from this recent paper entitled “Recursive Reasoning with Tiny Networks”:

This is a new neural network architecture that uses 7M parameters and achieves 44.6 on ARC-AGI1 which is more than nearly ALL of the frontier language models (besides grok, which does better but using an eye popping 254,857x more parameters).

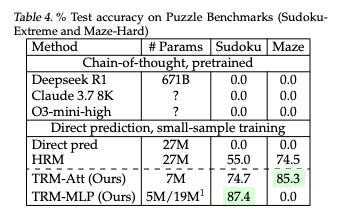

Things get even more stark for solving Sudoku or finding ways out of mazes:

On the surface, this feels like the wrong comparison: Claude 3.7 was one of the best coding assistance models when it came out and yet it’s terrible at these tasks… doesn’t that suggest that these tasks are not really useful for programming?

I believe that Claude’s utility is derived from its ability to ‘stay on task longer’ (aka instruction coherence) rather than anything else. The reason for this series of posts to exist is about me trying to find a way to explain to others why I feel that way.

A geometric model of programming

To do that, I need to introduce a model of programming that is forming in my head that is visual and intuitive even for those that never programmed a computer before (or don’t really care about it).

Let’s imagine that our programming world is a plane and that our programming tasks are about composing geometric shapes on this plane to achieve goals.

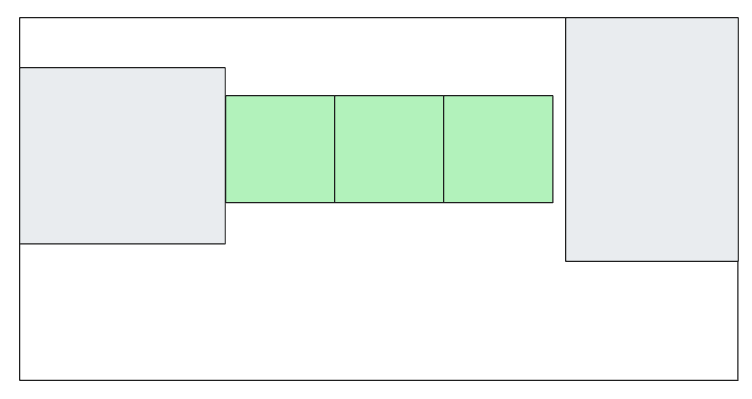

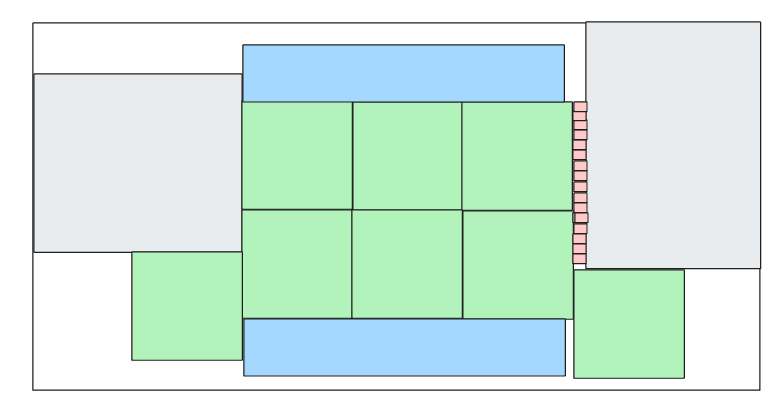

Let’s start with something simple like this:

where the gray islands are part of the land and are immutable (constraints). There are ants on the island on the left (their nest) and there is food on the island on the right. The ants are blind (they can’t see the land) but can smell the food and randomly work toward it. The white part is lava and kills the ants. Our goal is to make ants feed find the food and come back to their nest to feed.

We can build a bridge between these two islands by composing shapes we can find or make new ones on our own. Finding shapes is easier because making new shapes requires more work and more knowledge.

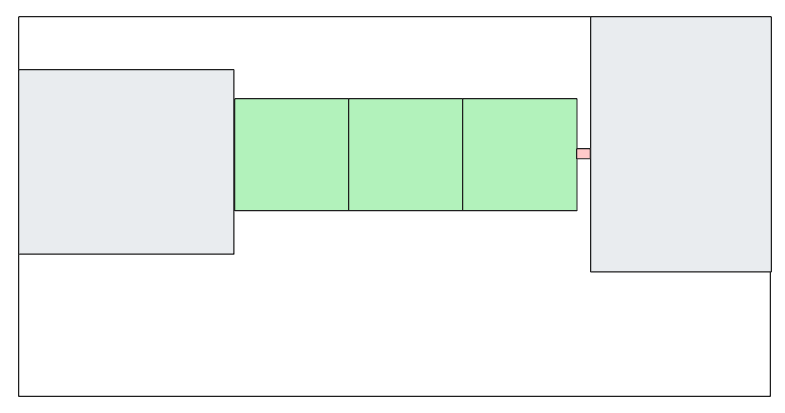

We start by looking around and we find this first existing piece of code that we believe can do the job, so we lay down a few copies of it:

We run the simulation and all the ants die. We find out there is a gap, so we have to use other components to fill that gap (we can’t overlap them). We can either find them or make them.

But here’s the kicker: we don’t have a measuring tape, the only way to know if our bridge actually works is to see if the ants are able to thrive or not.

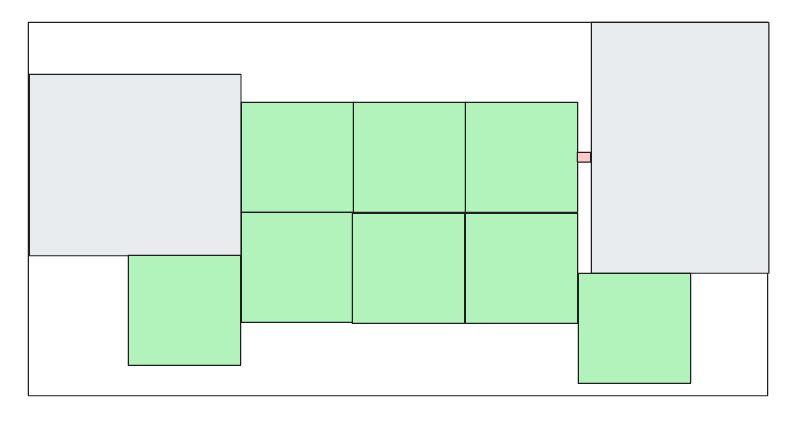

So, we can eyeball it and make this smaller square, fit it there and see if the ants are able to find their food. We keep doing this until they do and we come up with this which brings us further toward our goal.

There are several valuable things in this simple model:

it shows how programming is not just about creation but also about reuse (the green blocks already existed, we just used them but we had to find them, the red block is the “gap” we had to write ourselves, but maybe there was already a component that fit perfectly that we didn’t know existed!)

it shows it can be tricky to understand ahead of time what “works” (imagine doing woodworking without any measuring tools!)

it shows production risks (as not all uses will follow the same trajectory and some will work and some won’t and fall thru the gaps)

Our first bridge is effectively our “happy path” or “prototype”. Making our software “production ready” means saving as many ants as possible from the lava.

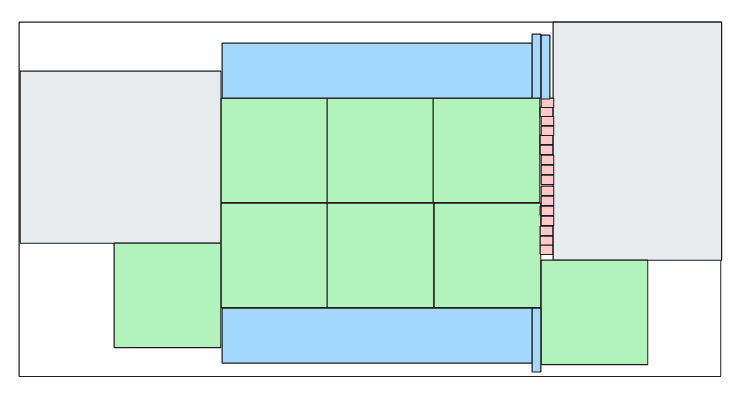

So our task changes from “bridging” to covering as many potential random walk paths from the source to the food and back. This other solution, for example

does nothing to help our happy path bridge, but saves more ants from falling into the lava and dying after leaving their island on the left and we didn’t have to create any more software, we just reused the existing block we already had.

But it doesn’t do much to save the ants as they get closer to the food on the right (and fall into the gap), so we could take our red component and use that to try fill the gap:

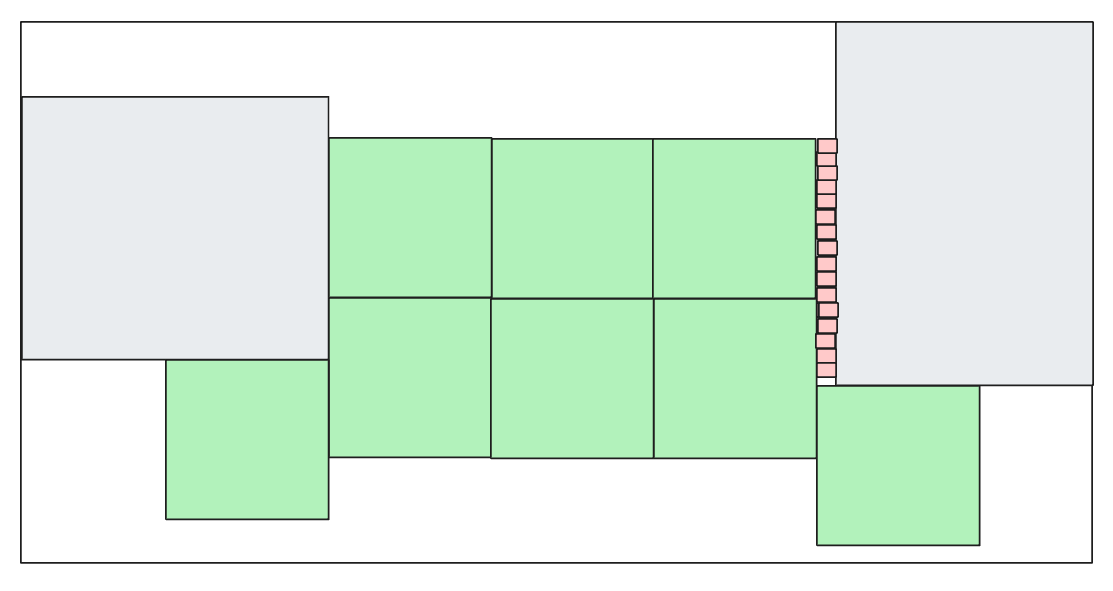

But at this point we’re out of easy options to improve things (remember, we have no way of measuring these gaps, so we have no idea how many red squares we would have to put to fill the plane or whether gaps would remain):

we can look stop here and accept the current rate of dying ants as “cost of doing business”

we can try to move the green and red blocks around to see if there are better ways to cover the gaps (for example, we could move the red blocks all a little below to cover that tiny gap at the bottom of the row)

we can try to add more red blocks around the green ones (but we would have no idea how “far” we are at closing those gaps)

we can try to look for new blocks to see if they help us cover things better

we can write another block and see how much more we can cover with it

People that have never programmed computers professionally feel that the job is to come up with those little red blocks, but really that’s only how the job starts.

The valuable (and difficult) part is to make the call about what to do next when all the easy options have been exhausted (and inspire trust in others that, indeed, that is the optimal choice forward given what we know).

Enter the minions

This model is good for some things but bad for others.

For example, it is so simple that it feels possible to build a machine that can try to tessellate the plane by moving blocks around randomly and brute-force its way thru a workable solution (a Tetris solver, basically).

In the real world, this would be the equivalent of randomly copy/pasting pieces of source code together and feed it into a compiler to see if it would generate a program that passed our tests (the way, say, evolutionary algorithms work). This wouldn’t work because:

the number of “test runs” we would have to execute to achieve anything would be astronomical (like the universe would die before we could find a solution)

there is no way to know if the program is getting “closer” to a solution or not (even a single wrong character can destroy code that would be perfect otherwise).

there would be no way for us to influence the outcome or to steer the system toward a solution if we only vaguely knew something a solution

In fact, a computer programs that plays Tetris well is trivial to conceive while a computer program that plays Go well is not and it all has to do with the size of the space of potential moves and how to operate “much better than random” in it.

LLMs change this picture because:

they are “better than random” at selecting pieces of code that can help us bridge or cover the plane

we can steer and nudge their behavior with natural language

My point is that these two things, alone, dramatically change the energy landscape of software development EVEN if the LLMs depth of understanding about what these blocks of code are actually doing is very shallow.

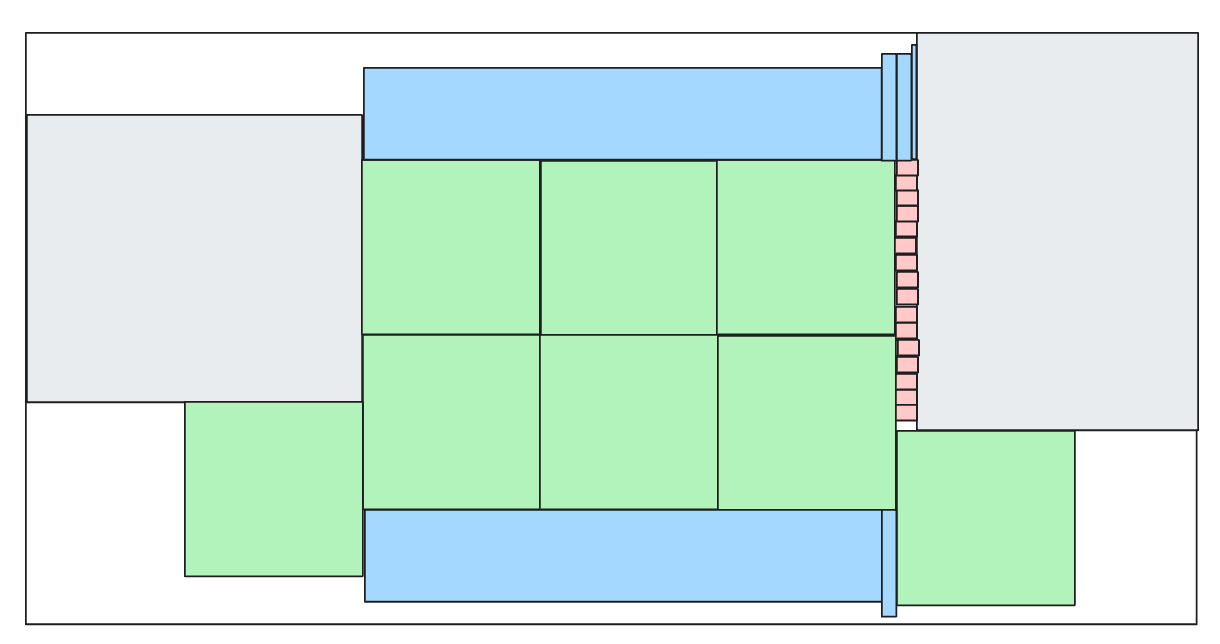

Let’s get back to where we left off but now we have coding minions at our disposal.

We can describe our situation and our constraints (in natural language), add our current solution to their context (in structured language), describe (in natural language) the lists of tools they can use to look up shapes and they tools they can use to run the program and see if the ants feed, wire them up to those tools and start.

We get something like this:

which saves some ants but not really that much (note how the LLM was able to find a block that fit on both sides but without closing the gaps). We run it again and now it comes up with this

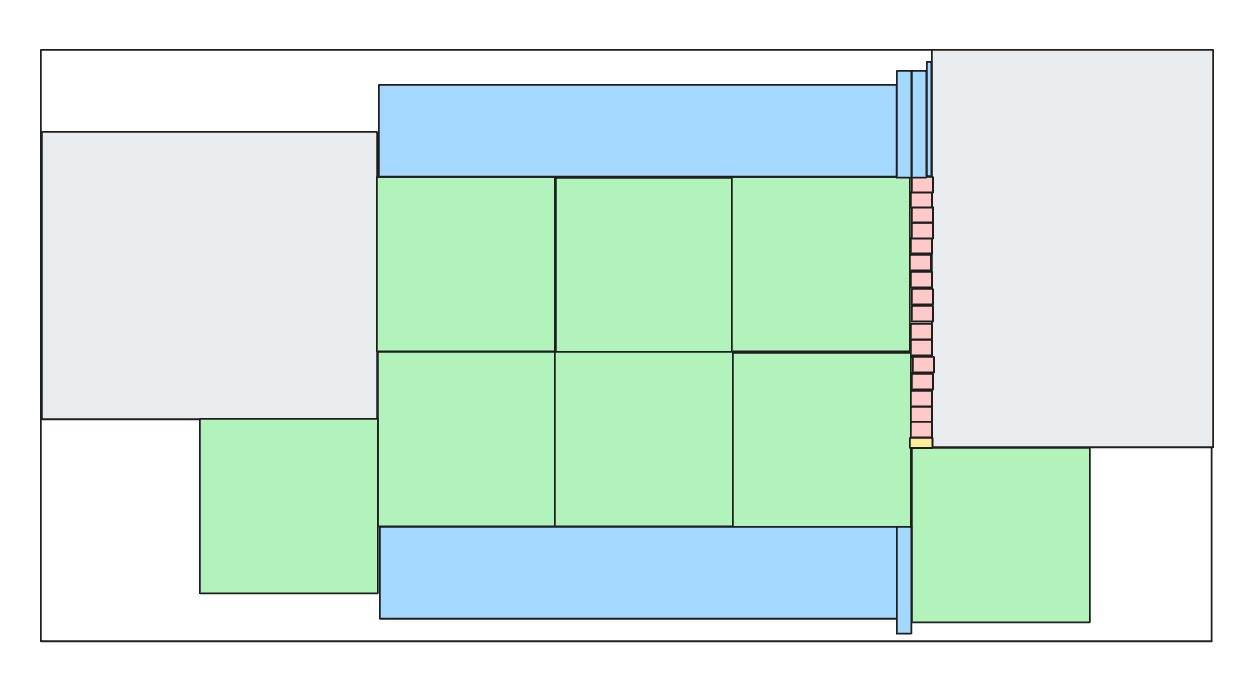

which closes the gap at the bottom but not at the top. Finally, we get to this

which closes the gap at the top, and we can come up with our own tiny block (in yellow) to fill even that edge case:

We won’t save all of the ants, but at this point we feel it’s good enough and we can launch it in production.

This is how coding with an LLM feels like.

This is very different than a random evolutionary algorithm because we have created a gradient by creating a feedback loop between probabilistic “better than random” guesses and deterministic validation nudges. The key is NOT how much better than random the guesses are (how intelligent those code blocks are that the model finds or comes up with) but how quickly/effectively the system is able to converge to a solution that passes our deterministic validations.

Granted: the more “intelligent” the agent is, the better the guesses and the fewer nudging loops we have to execute. But it’s very useful to realize that even with relatively “dumb” guesses, as long as the system is able to be nudged effectively by the natural language output of the program validation systems we had already built to nudge humans (compilers, linters, tests), we can converge to useful solutions.

This, IMO, explains how Claude is such an effective coding model even if it is incapable of solving basic CSPs: the ability to “stay on task” longer is the key property here, not how good the “coding guesses” are.

What does this mean, in practice? How can we make use of this model to help us code better and more effectively? Stay tuned for more in part 2.